Guillotine Linked to Marie Antoinette on Display

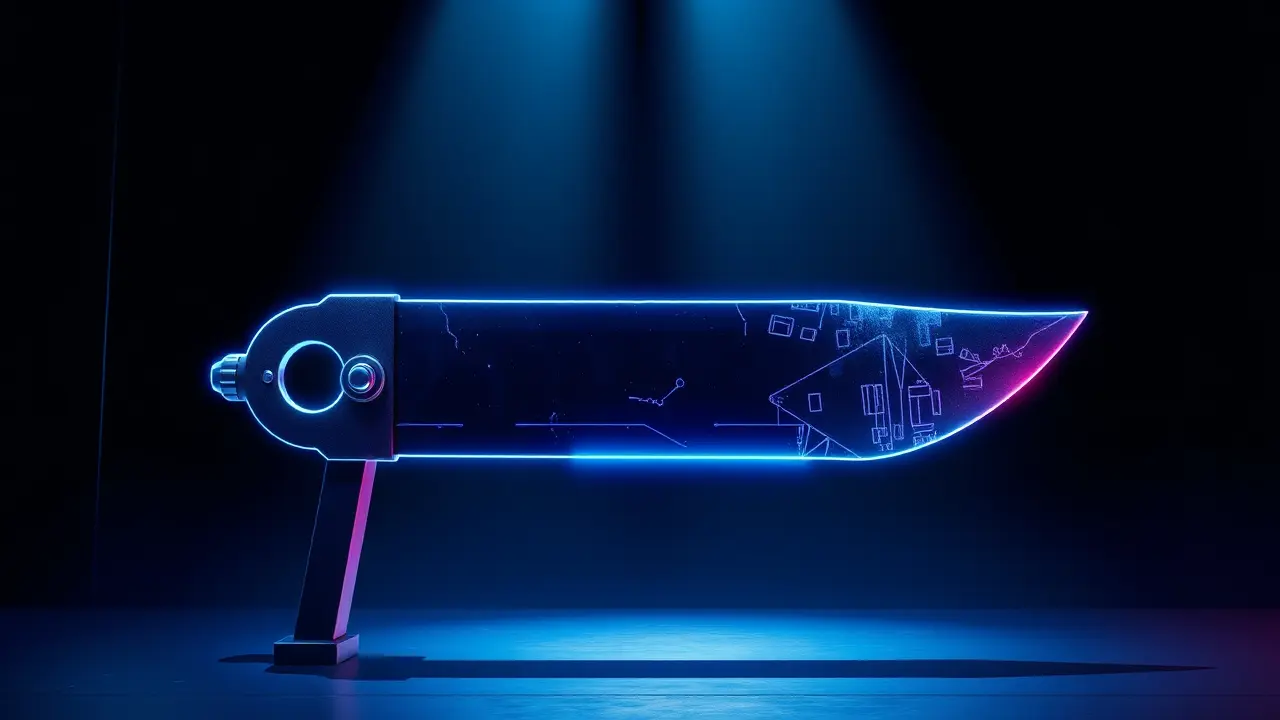

The stage is now set at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum for one of history’s most chilling and dramatic final acts, as the guillotine blade long associated with the execution of Marie Antoinette takes its place in the spotlight, an object of grim fascination that cuts through the centuries with the sharpness of the tragedy it represents. This isn't merely an artifact behind glass; it is a prop from a real-life tragedy of operatic proportions, a piece of the set from the day the music stopped for the last Queen of France, whose story of extravagant glamour and devastating downfall continues to captivate as powerfully as any Broadway epic.To stand before this instrument of revolutionary justice is to feel the ghost of that October day in 1793 on the Place de la Révolution, to hear the roar of the crowd that had once cheered her as the Dauphine now baying for her blood, a public spectacle where the former archduchess of Austria, once the embodiment of the Ancien Régime's opulence, ascended the scaffold with a dignity that, in its final moment, transformed her from a vilified symbol of excess into a figure of poignant, tragic martyrdom. The guillotine itself, promoted as a humane and egalitarian machine of death, became the great leveler in a society tearing itself apart, its falling blade a brutal curtain call on a world of divine right and aristocratic privilege, and its presence in a museum of art and design forces a confrontation not just with a singular death, but with the entire brutal theater of the French Revolution—the passionate scripts of Enlightenment philosophy twisted into the bloody drama of the Terror, where figures like Robespierre and Danton played leading roles in a production that consumed its own cast.The exhibition surrounding this blade provides the essential backstory, the acts that led to this climax: the Diamond Necklace Affair that scandalized a nation and painted the Queen as irredeemably decadent, the flight to Varennes that sealed the royal family’s fate, the imprisonment in the Temple tower that was their final, grim dressing room before the last performance. Historians and curators, like directors offering commentary on a classic play, debate the precise provenance of this very blade, a macabre detail that only deepens its mystique, while the V&A’s decision to display it raises profound questions about how we memorialize violence and whether such objects should be revered as history or viewed as warnings, a conversation as relevant today as the echoes of revolutionary fervor still heard in modern political upheavals. This single piece of sharpened metal is more than a relic; it is the climax of a human story of rise and fall, a tangible connection to a past that shaped our modern world, and its display ensures that the complex, haunting legacy of Marie Antoinette—both the frivolous queen and the courageous woman—will continue to command our attention, holding the audience captive long after the final curtain fell.

JA

Jamie Larson123k3 hours ago

wow that's heavy tbh can't imagine seeing that thing in person

0