Calls for UK government to pardon women executed for witchcraft

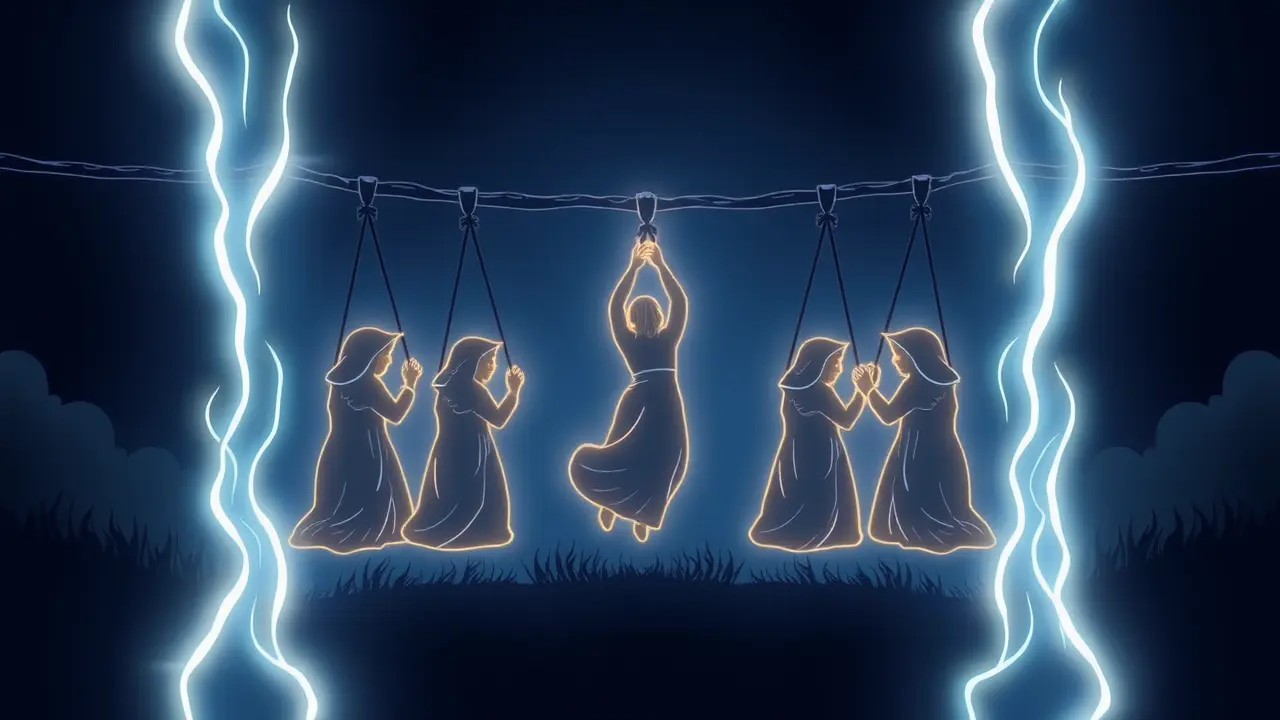

A quiet, persistent injustice, centuries old, is being dragged into the modern light of day as a council leader has formally petitioned the Home Secretary for a general pardon for the hundreds of women executed for witchcraft in the 16th and 17th centuries. This is not merely a historical footnote; it is a profound reckoning with a period of state-sanctioned gynophobia, a campaign of terror that systematically targeted women who were often the most vulnerable in their communities—the elderly, the poor, the outspoken, the healers.Consider the chilling case of 30 July 1652, on Penenden Heath in Maidstone, Kent, a day that saw seven women—Anne Ashby, Mary Brown, Anne Martyn, Mildred Wright, Susan Pickenden, Anne Wilson, and Mary Reade—hanged together in a single, grotesque spectacle. Their alleged crimes, as recorded by their accusers, read like a primer in patriarchal panic: they were charged with 'bewitching to death' a ten-day-old infant, the child's mother, and another three-year-old, acts that channeled the community's uncomprehending grief into a lethal fury.More insidiously, several were accused of having 'carnally known' the devil, a charge that weaponized female sexuality itself, transforming it into a monstrous compact for supernatural power. This case exemplifies the dynamics at play: these women were scapegoats for societal ills, from infant mortality to crop failure, and their convictions were often secured through coerced confessions, spectral evidence, and the testimony of neighbors gripped by fear and superstition.The push for a pardon today is a feminist act of restorative history, an acknowledgment that these women were not villains but victims of a misogynistic moral panic. It forces us to examine the modern echoes of such persecution, where women who challenge social norms or wield unconventional influence are still metaphorically—and sometimes literally—burned at the stake of public opinion.The campaign connects to a broader, global movement, following similar posthumous pardons in Scotland and Switzerland, signaling a growing understanding that historical wrongs, if left unaddressed, cast long shadows. For the descendants of these women, a pardon is not an empty gesture but a symbolic cleansing of their family names, a declaration that their ancestors were not evil but were murdered by a system that failed to protect them.It raises complex questions about how a nation confronts the darkest chapters of its past and whether official absolution can ever truly heal such deep-seated wounds. The government's response will be a telling indicator of how it views the legacy of violence against women and its willingness to correct a historical injustice that, for many, still feels painfully contemporary.

It’s quiet here...Start the conversation by leaving the first comment.

© 2025 Outpoll Service LTD. All rights reserved.